Airway management is one of the most popular topics of discussion among ER doctors. This case will certainly spark debate and strong opinions from many readers. There were multiple factors that all contributed to this patient’s death. The purpose of this review is not to use hindsight to harshly judge the clinician, but to find areas of improvement to enable the reader to take better care of their patients when they find themselves in a similar situation.

Decision to Intubate

The patient presentation is a classic emergency situation; she is critically ill and there is no time to collect information or prepare. These are the situations in which EM doctors must excel, make rapid decisions, with no backup, under uncertain conditions. The clinician in this case makes a definitive decision to intubate the position almost immediately. Nasal intubation is attempted first in a hallway bed. The fact that this first nasal attempt was “unsuccessful due to lack of patient cooperation” leads the reader to question if the patient could have been taken to an emergency bay and undergone a more conventional oral intubation. Most descriptions of nasotracheal intubations describe more controlled circumstances that require time for preparation (here and here). Nasotracheal intubation in the code or peri-code situation is atypical.

Medications

Another concerning aspect of the intubation is the medications used. No medications were given over the course of the first two intubation attempts (one nasal and one oral). The patient was not in cardiac arrest during these first two attempts. 5mg of Versed was given prior to the third attempt. The hospital at which this occurred did not allow paralytics to be given in the ED. This may have played a significant role in the multiple failed intubation attempts, leading to placement of a King airway, and eventually the patient’s death. There is good evidence to show that use of rapid sequence intubation with both sedative and paralytic is associated with higher first pass success rate. This benefit has been shown in the ICU as well. Preventing residency-trained EM doctors from using paralytics for RSI in the ED is tantamount to institutional malpractice and indicates a dangerous disregard for the safety of patients.

King Airway

The King airway is a supraglottic airway tool that can be inserted blindly into the patient’s mouth with the goal of providing ventilation and oxygenation through ports directed at the patient’s vocal cords.

Use of the King airway is mostly in the prehospital setting, but they are often available as back-up devices in an ED. Many EM doctors prefer alternative supraglottic devices such as the iGel or LMA. It is difficult to know what equipment and options the doctor had available after attempting to intubate the patient. It is unclear if he was using video or direct laryngoscopy, if a bougie was available or considered, or if she could be easily ventilated with a bag-valve mask. The fact that the hospital wouldn’t allow paralytics to be used in the ED is a strong indicator that the facility may not have been well prepared to deal with an airway emergency of this nature. A lack of necessary drugs and equipment will limit the ability of the most brilliant clinician.

The use of the King airway in this case seems to have temporarily improved the patient’s status. Following placement of the King airway, her oxygen saturation was 97%, but it slowly began to decline over the next 90 minutes and was down to 81% by the time she departed the ED. The next available vital signs, on arrival to the subsequent hospital, revealed a pulse ox of <40%. The King airway performed its job as a temporizing measure, but not surprisingly failed to provide adequate oxygenation over a longer time period. It is unclear if the clinician ever considered obtaining a definitive airway after temporarily stabilizing the patient with the King airway.

King Exchange

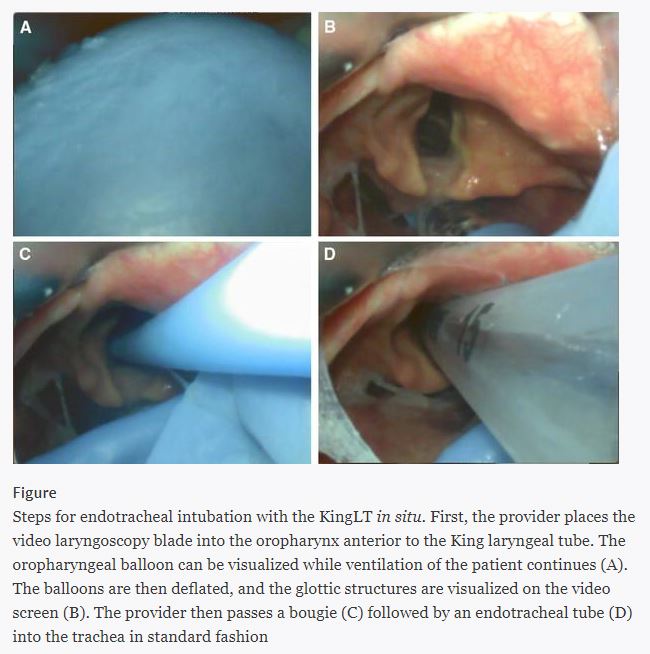

For the EM doctor, understanding how to safely exchange a King airway for a definitive airway is a critical skill that will likely be used more often than placing the King airway. Many facilities have policies that dictate the method for exchanging a King airway. There is some literature to suggest that advanced airway techniques are usually required to exchange a King airway. However, this has been challenged by the use of a simple technique that can be attempted. Insertion of a video laryngoscope into the patient’s oropharynx, followed by deflation of the King airway pharyngeal balloon, may enable safe and rapid exchange. This technique is shown below and taken from this paper.

Exchanging the King device for a definitive airway in the ED would have involved some risk, but with oxygen saturation declining to the low 80s, was indicated prior to transfer.

Teamwork

One positive aspect of this patient’s care is the response and preparedness demonstrated at the receiving hospital. Both anesthesia and pulmonology were available at the bedside as she arrived on the helipad. Their immediate assistance was necessary and they were prepared to care for the patient. Many EM physicians know the feeling of a specialist dragging their feet. When a physician requests help for an airway emergency, the only acceptable response is “I will be there as fast as possible”.

Transfer Process

The process of transferring this patient raises a few issues that should be addressed. While the importance of this issue may seem less relevant than the plaintiff’s attorneys would lead you to believe, it is still worth consideration. In my opinion, the response of the first doctor (Dr H, the defendant), was appropriate. This patient was an appropriate transfer to an academic medical center. It is frankly disappointing that the process for transferring a critically ill patient to an academic center would result in a response of “We’ll call you back later”. This may be an acceptable response for non-emergent transfers, but not in this situation. This patient needed a rapid transfer, and the systems in place may have contributed to her death.

Another disappointing aspect was the response of the first cardiologist, suggesting that the ED doctor should consult the patient’s outpatient cardiologist before transferring her. This a bizarre and unacceptable response. The patient is critically ill, has a prospectively-recognizable impending airway disaster, and is in a facility that obviously cannot provide the level of care she needs. Sending the ED doctor on a wild goose chase to track down her outpatient cardiologist is the last thing that needs to happen. Even if the patient’s cardiologist could be contacted immediately, he would be useless to the situation at hand. Thankfully, the second cardiologist the ED doctor contacted appreciated the gravity of the situation and responded appropriately.

Each hospital functions differently, but the best person to contact in this situation is usually the intensivist. Especially in a referral center, the ICU doctor is well prepared to manage these cases and generally will accept critically ill patients from outlying hospitals without ICU capabilities.

As with every case, there are multiple factors that influenced this patient’s bad outcome. There are multiple issues at the individual level, including the initial attempted intubation route and inappropriate specialist recommendations. These decisions are strongly influenced by systems issues that force individual doctors into unsafe situations. Too often, the blame for the bad outcomes created by institutional policies is laid at the feet of the individual physician. Avoiding these bad outcomes in the future will require improvements at both the individual and system level.